We all know the romance genre has conventions and guidelines that set it apart from other types of stories. And with those guidelines comes a vocabulary. Here at Romance HQ, we use that vocabulary every day, and sometimes we take it for granted. So we came up with a partial list of definitions so you, too, can become an expert in the language of love (or at least writing about it)!

This glossary is a work-in-progress; if you don’t see a particular term here, let us know in the comments below!

Romance Glossary

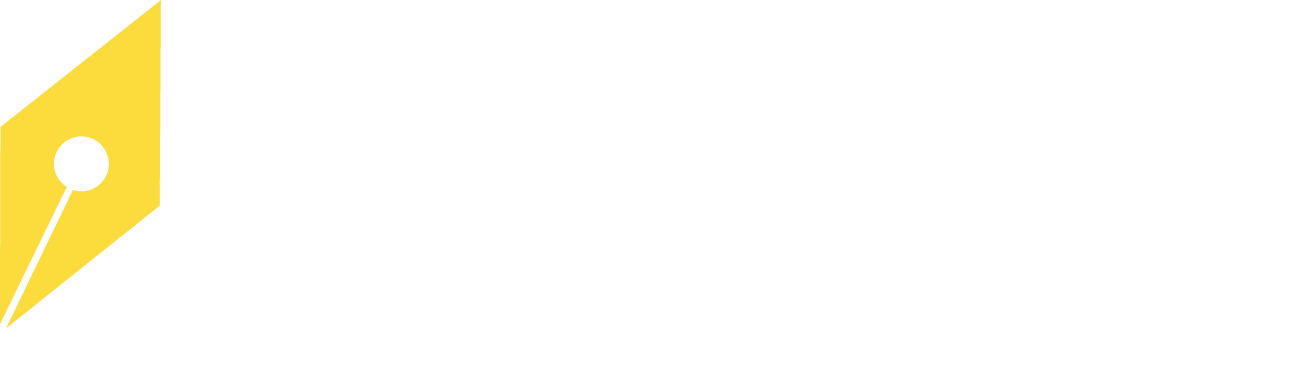

Alpha Hero: Strong, assertive hero who is in charge and oozes power. He knows he wants the heroine and will do anything to be with her. Think the CEO who’s in charge of everything in the boardroom—and out of it.

Aspirational: Describes a story that sweeps us away, and that readers will aspire to. Whether it’s exotic locations, rich alpha heroes or a glamorous lifestyle, we’re looking for the stuff of daydreams!

Black moment: This is the moment near the end of your story where all your hero and heroine’s issues come to a head, and the reader is left wondering how on earth they will ever find their happy ever after.

HEA: An abbreviation for Happy Ever After.

Happy for Now: An increasingly common ending in certain romance novels, where the hero and heroine overcome their obstacles in order to be together, but they don’t necessarily get married or work out every kink in their relationship.

Head-hopping: When the point-of-view bounces from the hero to the heroine’s thoughts without an obvious break in the story/scene. Quick POV switches can be difficult for readers to keep up with and create inconsistency.

Hook: A scenario, plot device or other element that draws a reader into a story. A hook can be anything from character type (cowboy hero!) to setting (elephant research centre in Kenya!) to inciting event (heroine’s inn burns down!) or any other new, interesting or compelling aspect of the story.

Internal conflict: The emotional issues which stem from your characters’ backstories and create barriers to their relationship in the front story.

Inciting moment: The scene or situation that throws your hero and heroine together and gets those sparks flying!

Miniseries: Two or more books within the same Harlequin series or imprint that are connected by setting, characters or other common elements. Also known as connection or continuity.

Obstacle: What keeps the hero and heroine apart even as they’re falling in love. Obstacles can be internal or external, and a successful romance novel will rely on both.

POV: Abbreviation of point-of-view. Is the story/scene being told in first-person or third-person? Are we in the hero or heroine’s head?

Sensuality level: How sexy your story is—whether the bedroom door is open, closed, non-existent (bedroom? what bedroom?) or somewhere in between.

“Show don’t tell” : Revealing your characters’ personalities by showing how they react emotionally to different situations and introducing them to the readers gradually, rather than merely stating how they’re feeling in any given moment.

Series: One of the twelve categories or lines at Harlequin. Each series has a reader promise—i.e., mystery with romance, clean romance—a regular publishing schedule and a word count. Different editors work on different series, and when you submit to Harlequin, you’ll want to target one of the series specifically, be it Presents, Historicals, Heartwarming, etc.

Stakes: What the hero and heroine each stand to lose in loving each other. Stakes can be emotional (a single dad who’s worried about his kids’ well-being if he starts a relationship with the heroine) or more concrete (a secretary who could lose her job if she falls for the CEO), though the best romances combine both types.

Trope: A trope is a time-tested scenario or plot device that appears again and again. Secret babies or heroine-in-jeopardy are examples of romance tropes. We also love to see twists on classic tropes in Series (i.e., the heroine rancher vs. the city boy hero, instead of the reverse).

Voice: The distinct way(s) an author communicates with a reader. Writers can control many elements of their voice, from sentence structure to imagery to verb tense to the tone or intent of a particular scene. But just as everyone has a unique speaking voice, every writer’s voice will have some instinctual, intrinsic elements that are hers alone.

Join the conversation on Twitter and follow @HarlequinSYTYCW.

(Updated from previously posted version)